CHAPTER 14.1

Where Do Shoes Come From?

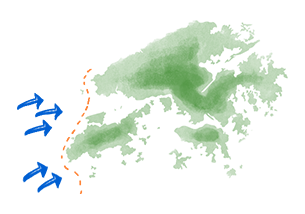

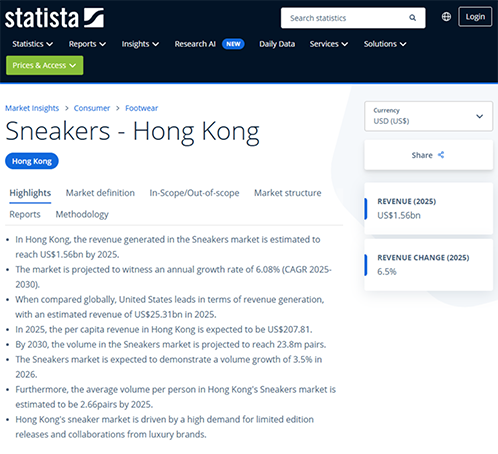

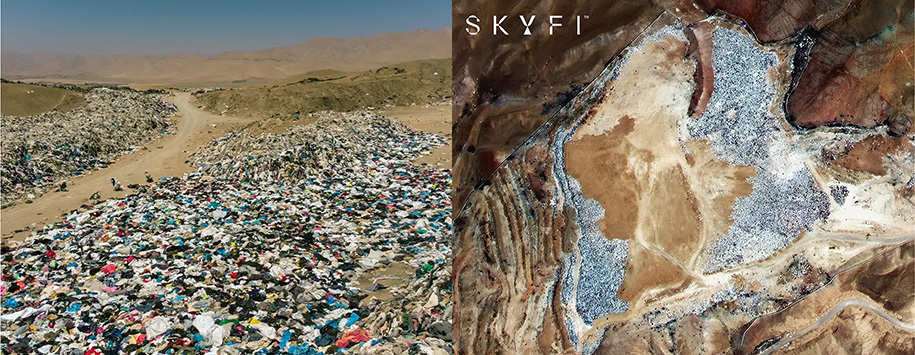

The Environmental Protection Department (EPD)’s 2015 report, Investigation on the Sources and Fates of Marine Refuse in Hong Kong, categorizes marine debris into eight major types. Shoes are not listed as a distinct category but are grouped with clothing, towels, and hats under “Cloth.” The report notes that of the approximately 15,000 tonnes of marine debris collected annually in Hong Kong, “Cloth” constitutes no more than 2%, or roughly 300 tonnes. This makes it challenging to discern the specific contribution of shoes to the total.

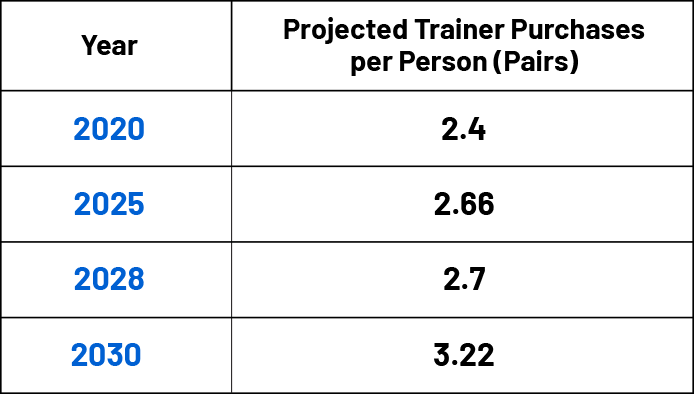

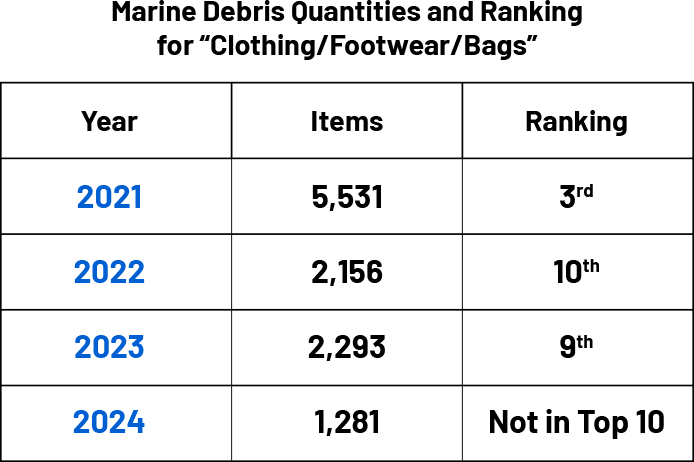

Data compiled from:My Nature Diary

The 2% may seem minor, but it’s far from insignificant. Since 2021, My Nature Diary, a platform dedicated to marine debris issues, has meticulously catalogued sea waste, revealing that “clothing/footwear/bags” number in the thousands annually and have repeatedly ranked among Hong Kong’s top ten marine debris types.

The variety of shoes found in marine debris is vast. Based on nearly a decade of beach cleanups by The Green Earth, flip-flops dominate, followed by sandals, canvas shoes, hiking boots, high heels, pointed-toe shoes, and Crocs. Brand-wise, there’s no shortage of name-brand trainers like Adidas, Nike, and New Balance, alongside counterfeit Gucci sandals. Beaches resemble a miscellaneous shoe stall, with everything imaginable.

Flip-flops, lightweight and buoyant, can float across oceans, so their abundance is unsurprising. However, it’s worth noting that heavier shoes likely sink to the seabed before being noticed, suggesting the total weight of shoe debris far exceeds the 300 tonnes reported for “Cloth” in EPD’s report.

You might wonder: unlike single-use items like plastic bottles, cigarette butts, or food packaging, how do shoes and clothes end up numbering in the thousands? To answer, let’s first explore the sources of marine debris in Hong Kong.

Waterfront and Water-Based Activities: Shoes are often swept away by waves during beach play or lost while kayaking. Operators of speedboats ferrying tourists to outlying island beaches note that passengers wading to board, often juggling beer, children, or distracted by taking photos, frequently lose their shoes, joining the “flip-flop dropout club”.

Vessels: Items are accidentally or deliberately dropped from fishing operations (e.g., fish farms, fishing boats), yachts, cargo ships, or cruise liners. The latter is particularly deplorable.

Runoff from Rivers and Drainage Channels: Household waste, including shoes, is easily washed into rivers, especially during heavy rain or typhoons.

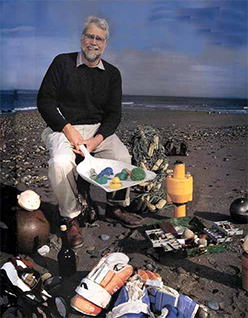

Shoes collected by My Nature Diary members in a single day at Fan Lau, Lantau Island, in 2021, totaling 1,645 pairs.

The striking “shoe array” in the image was collected by members of My Nature Diary during a 2021 cleanup at Fan Lau, Lantau Island. A record-breaking 1,645 shoes were gathered in a single day, with over half being flip-flops. The cleanup’s initiator Yeungs, known as “Sheeppoo” remarked, “That day, we were truly shocked by the sheer number of shoes.” Similar scenes have since been observed at other beaches, creating a spectacular sight.